Observation – Seeing Flashed Cards

c. Seeing flashed cards

Many important cards are flashed during a game. Players who see flashed cards are not cheating. Cheating occurs only through a deliberate physical action to see unexposed cards. For example, a player who is dealing and purposely turns the deck to look at the bottom card is cheating. But a player who sees cards flashed by someone else violates no rule or ethic. To see the maximum number of flashed cards. one must know when and where to expect them. When the mind is alert to flashing cards, the eye can be trained to spot and identify them. Cards often flash when—

- they are dealt

- a player picks up his hand or draw cards

- a player looks at his cards or ruffles them through his fingers

- a kibitzer or peeker picks up the cards of another player (peekers are often careless about flashing other players’ cards)

- a player throws in his discards or folds his hand

- cards reflect in a player’ s eyeglasses.

The good player occasionally tells a player to hold back his cards or warns a dealer that he is flashing cards. He does that to create an image of honesty, which keeps opponents from suspecting his constant use of flashed cards. He knows his warnings have little permanent effect on stopping players from flashing cards. In fact, warned players often become more careless about flashing because of their increased confidence in the “honesty” of the game.

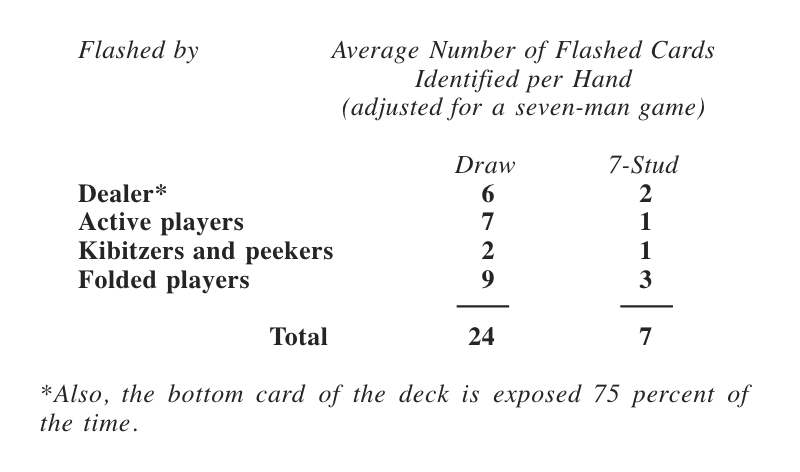

Using data from one hundred games, John Finn compiles the following chart, which illustrates the number of flashed cards he sees in the Monday night game:

These data show that in addition to seeing his own cards, John sees over half the deck in an average game of draw poker—just by keeping his eyes open. The limit he goes to see flashed cards is illustrated below:

Mike Bell is a new player. John does not yet know his habits and must rely on other tools to read him— such as seeing flashed cards.

The game is lowball draw with one twist. The betting is heavy, and the pot grows large. John has a fairly good hand (a seven low) and does not twist. Mike bets heavily and then draws one card. John figures he is drawing to a very good low hand, perhaps to a six low.

John bets. Ted Fehr pretends to have a good hand, but just calls—John reads him for a poor nine low. Everyone else folds except Mike Bell, who holds his cards close to his face and slowly squeezes them open; John studies Mike’s face very closely. Actually he is not looking at his face, but is watching the reflection in his eyeglasses. When Mike opens his hand, John sees the scattered dots of low cards plus the massive design of a picture card reflecting in the glasses. (You never knew that?… Try it, especially if your bespectacled victim has a strong light directly over or behind his head. Occasionally a crucial card can even be identified in a player’s bare eyeball.)

In trying to lure a bluff from the new player, John simply checks. Having already put $100 into the pot, Mike falls into the trap by making a $50 bluff bet. If John had not seen the reflection of a picture card in Mike’s glasses, he might have folded. But now he not only calls the bluff bet with confidence, but tries a little experiment—he raises $1. Ted folds; and Mike, biting his lip after his bluff failure, falls into the trap again— he tries a desperate double bluff by raising $50. His error? He refuses to accept his first mistake and repeats his error… Also, he holds cards too close to his glasses.

John calmly calls and raises another $1. Mike folds by ripping up his cards and throwing them all over the floor. His playing then disintegrates. What a valuable reflection, John says to himself.

[Note: Luring or eliciting bluffs and double bluffs from opponents is a major money-making strategy of the good player. In fact, in most games, he purposely lures other players into bluffing more often than he bluffs himself.]