Credit

2. Credit

Credit policies can determine the health of a poker game. The proper use of credit allows a faster betting pace and higher stakes. Since the good player is the most consistent winner, he is the prime source of credit and, therefore, exercises a major influence on the credit policies. He applies the following credit rule to poker games:

All debts must be paid by the start of each game.

No one may play while owing money from a previous game.

The above rule is effective in preventing bad debts that can damage or destroy a game. The credit rule also prevents a valuable loser from accumulating such a large poker debt that he quits the game and never plays again just to avoid paying the debt. When a loser is temporarily forced out of the game by the credit rule, he usually recovers financially, repays his debts, and then returns for more losses.

Enforcing the credit rule offers the following additional advantages:

- Provides a clear rule that forces prompt payment of poker debts.

- Forces more cash into the game, which means more cash available for the good player to win.

- Increases the willingness of players to lend money, which provides more cash for the losers.

- Detects players headed for financial trouble.

- Forces bankrupt players out of the game before serious damage is done.

The good player is flexible and alters any policy when beneficial. For example, he may ignore the credit rule to prevent a wealthy, heavily losing player from quitting the game. But he carefully weighs the advantages against the long-range disadvantages before making any exception to the credit rule.

By not borrowing money himself, the good player avoids obligations that could reduce his influence over the credit policies. If the good player loses his cash, he writes a check. A check puts more money into the game and sets a good example for using checks instead of credit. If the good player must borrow, he does so from a player who rarely borrows himself and thus would seldom demand a reciprocating loan.

a. Extending credit

The good player extends credit only for personal financial gain. He selectively extends credit for the following reasons:

- Available credit keeps big losers in the game. Steady losers who must constantly beg to borrow may quit the game out of humiliation or injured pride. But if big losers can borrow gracefully, they usually continue playing and losing.

- Opponents often play poorer poker after they have borrowed money.

- The good player can exercise greater influence and control over players who are in debt to him.

To obtain maximum benefits when lending money, the good player creates impressions that he—

- is extending a favor

- gives losers a break

- lends only to his friends

- lends only when winning and then on a limited basis

- expects other players, particularly winners, to lend money.

b. Refusing credit

Easy credit automatically extended by a winning player will make him the target for most or all loans. Automatic credit decreases the money brought to the game, which in turn decreases the betting pace. Ironically, losers often feel ungrateful, resentful, and often suspicious toward overly willing lenders.

Refusal of credit is an important tool for controlling credit policies. The good player selectively refuses credit in order to—

- prod players into bringing more money

- force other players to lend money

- make borrowers feel more obligated and grateful

- avoid being taken for granted as an easy lender

- enhance an image of being tough (when advantageous)

- avoid poor credit risks

- upset certain players.

c. Cashing checks

In most poker games, checks are as good as cash. The threat of legal action forces fast payment of most bounced checks. The good player likes to cash losers’ checks, because —

- money in the game is increased

- losers get cash without using credit

- his cash position is decreased, which puts pressure on other winners to supply credit

- losers are encouraged to write checks, particularly if resistance is offered to their borrowing, while no resistance is offered to cashing their checks.

d. Bad debts

A bad poker debt is rare. Losing players are gamblers, and most gamblers maintain good gambling credit. Some players go bankrupt, but almost all eventually pay their poker debts. When a loser stops gambling to recover financially, the best policy usually is to avoid pressuring him into paying his poker debt. Such pressure can cause increasing resentment to the point where he may never pay… or even worse, never return to the game to lose more money.

A house rule that allows bad debts to be absorbed by all players (e.g., by cutting the pot) has two advantages:

- Lenders are protected; therefore, all players are more willing to lend money.

- A debtor is less likely to welch against all the players than against an individual player.

Establishing a maximum bad debt that will be reimbursed by cutting pots is a wise addition to that house rule. Limiting this bad-debt insurance will—

- restrain excessive or careless lending

- provide a good excuse for not lending cash to a loser beyond this insurance level

- discourage collusion between a lender and a potential welcher

- avoid any large liability against future pots that could keep players away from the game until a large bad debt is paid by cutting the pot.

A gambling debt has no legal recourse (except debts represented by bad checks). A welcher, however, will often pay if threatened with a tattletale campaign. If he still does not pay, a few telephone calls to his wife, friends, and business associates will often force payment. The good player openly discusses any bad poker debt as a deterrent to others who might consider welching.

Handling credit is an important and delicate matter for John Finn. He must make credit available to keep the game going, but must limit the use of credit to keep cash plentiful. He must appear generous in lending his winnings, while appearing tough against players abusing the use of credit. John pressures other winners into lending their money and pressures losers into writing checks. He must prevent hurt feelings on the part of losers as he enforces the credit rule (described in Concept 63)…. All this requires careful thought and delicate maneuvering.

Sid Bennett is wealthy and loses many thousands of dollars every year. John takes special care of him. Usually Sid brings plenty of cash to the game, maybe $500 or $600. When he loses that, John gently pressures him into writing checks. Occasionally, Sid gets upset and refuses to write any more checks. He then borrows with gusto. Sometimes when he runs out of money, he scans the table for the biggest pile of money. Then, smash, his big fist descends without warning . . . he grabs the whole pile of money and peels off a couple hundred dollars. If the victim objects, Sid just grunts and looks the other way, but keeps the money. Most players grant him that liberty because they know he is rich and will always repay them.

Occasionally, Sid becomes bitter when suffering big consecutive losses and refuses to pay off his debts by the next game. John realizes that Sid might quit the game if the credit rule were applied to him. So if Sid owes him money under those conditions, John says nothing and lets the debt ride until the following week. But if Sid refuses to pay money he owes to another player, John pays off the debt while reminding everyone that debts cannot be carried over. Sid usually pays John later the same night or the following week. With his tantrums appeased, Sid happily goes on to lose many thousands more.

While lax with Sid, John Finn rigidly enforces the credit rule against other players. He is particularly tight about extending credit to Ted Fehr because of his poor financial condition. John often refuses him credit and makes him write checks That tough policy forces Ted to quit when he is broke. Then when he accumulates enough money, he returns to the game, pays off his debts, and loses more money.

When Ted quits for several weeks to recover financially, a losing player occasionally complains about holding one of Ted’s debts or bounced checks. John offers to buy the debt or check at a 25 percent discount. Such transactions keep everyone happy: they give the losers more cash to lose, and John acquires extra profits from the stronger players.

At times, John Finn refuses to lend money to anyone. Such action forces others to lend their cash. At other times, he puts on subtle displays of generosity. For example, if players with good credit run low on money, John advantageously reduces his cash position by handing them money before they even ask for a loan. Everyone is favorably impressed with his acts of fake generosity.

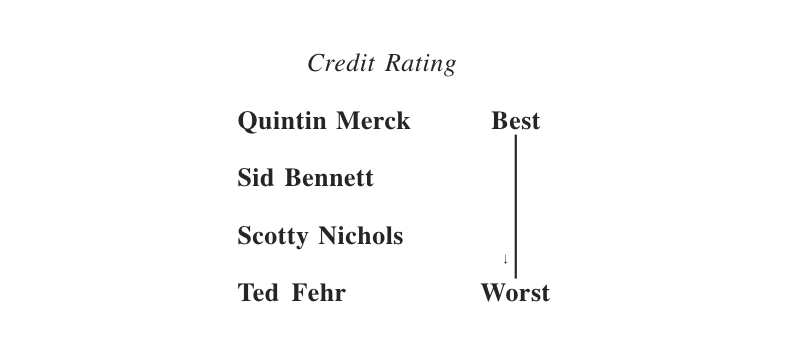

In John’s notebook is the following list:

When a player writes a check, John usually makes a quick move to cash it. To him, checks are often better to hold than money because cash winnings are more obvious targets for loans than are check winnings.