Controlled Money Flow

3. Controlled Money Flow

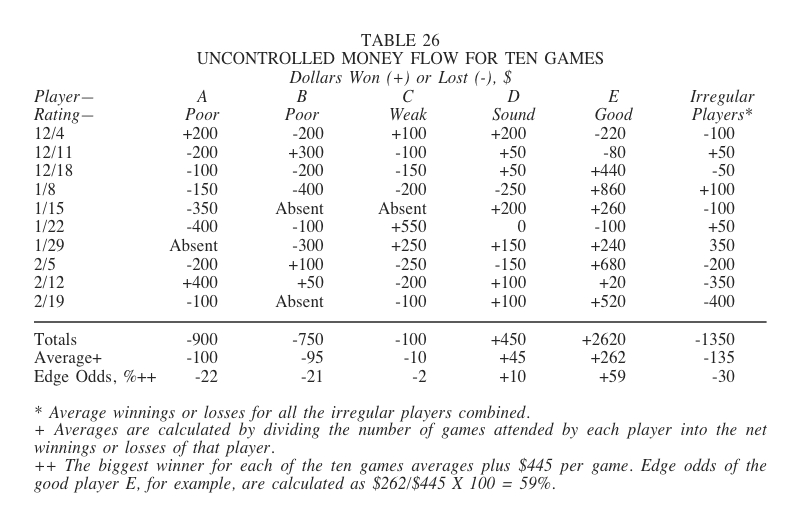

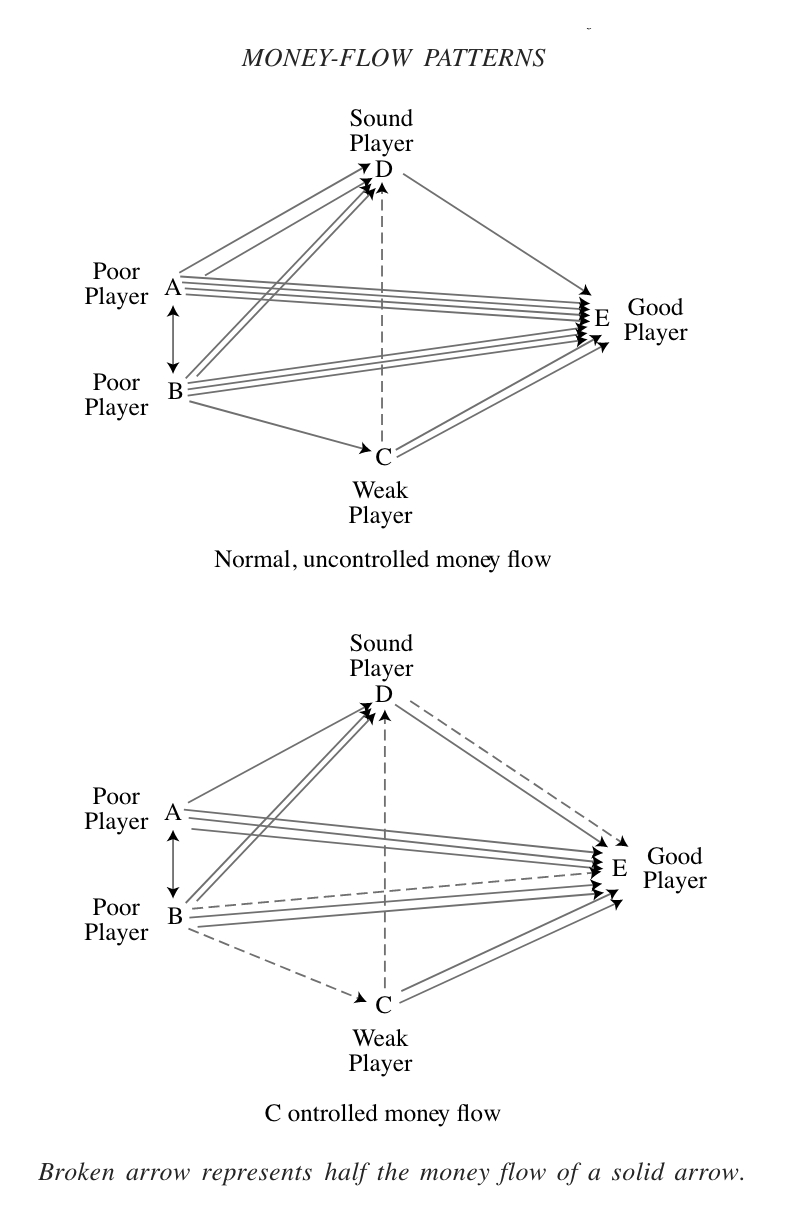

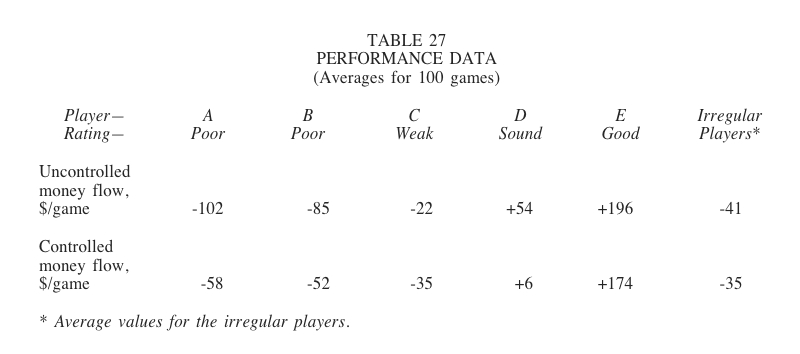

The good player evaluates the money-extraction patterns on both a short-term and a long-term basis. If a controlled pattern seems desirable, he then determines how the money flow should be altered (extent and direction). In a controlled pattern, he usually extracts money more evenly from his opponents … he extracts less from the poorer players and more from the better players. Controlled money flow shifts everyone’s performance, as shown in Table 27.

That controlled pattern costs the good player an average of $22 per game. But if the money flow were not controlled, the continued heavy losses of poor players A and B could destroy the game, costing the good player his $17,400 winnings over those one hundred sessions. That $22 per session is his insurance premium for keeping the game going at high-profit conditions. The good player keeps performance records to determine the cost, value, and effectiveness of his control over the money flow. Money-flow control normally costs him 10-15 percent of his net winnings.

The good player usually takes control of the money flow during the early rounds, when his betting influence can be the greatest at the lowest cost. He alters the money-flow patterns by the following methods:

- He helps and favors the poorest players at the expense of the better players whenever practical.

- He drives the poor players out with first-round bets when a better player holds a strong hand. And conversely. he uses first-round bets to keep the better players in when a poor player holds a strong hand.

- He avoids, when practical, playing against a poor player after everyone else has folded in order to decrease his advantage over the poor player at a minimum cost. He also tries to make his least favorable plays (e.g., his experimental, image-building, and long-term strategy plays) against the poorest players.

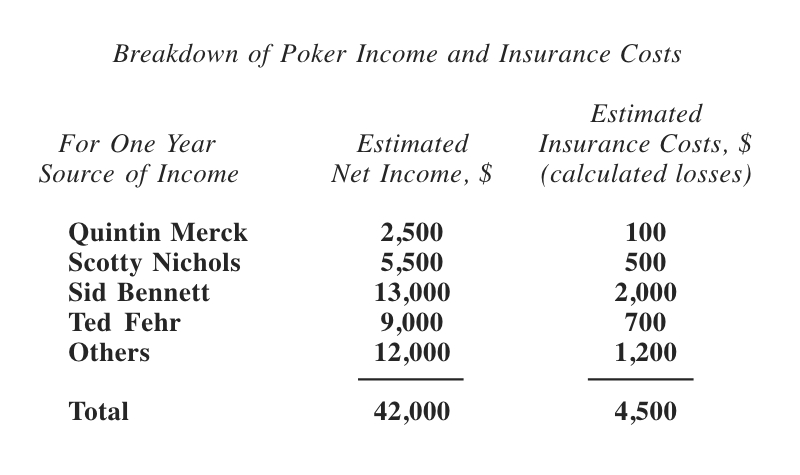

John Finn spends some of his winnings to hold big losers like Sid Bennett and Ted Fehr in the game. The following data from John’s records indicate that his insurance costs are profitable investments.

Without paying that insurance, John theoretically could have won $4500 more during that year. Yet without the insurance, the greater psychological and financial pressures on the big losers might have forced them to quit . . . and each big loser is worth much more than the entire $4500 insurance cost. Also, if several big losers had quit, the poker game could have been destroyed. John, therefore, considers the insurance cost an important and profitable investment.

How does he spend this $4500? The money buys him the valve that controls the money flow. He watches the losers closely. When they are in psychological or financial trouble and on the verge of quitting, he opens the valve and feeds them morale-boosting money until they are steady again.

Winning players are of little value to John. Since there is no need to help them or boost their morale, he keeps the valve closed tight on them. He may even spend money to drive them out of the game if they hurt his financial best interests.

John Finn never spends money on any player except to gain eventual profits.